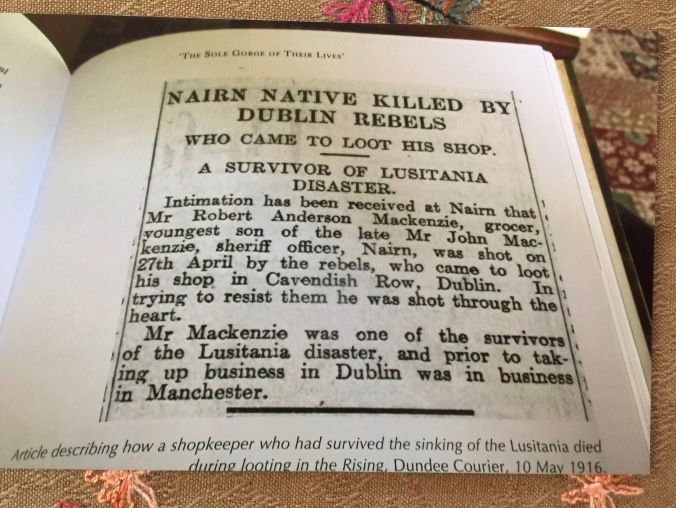

Presented by Kathleen Macfarlane

One of the many boxes of mesolithic flints Kathleen has dug up in her garden.

My story begins in the 1990s when I retired from teaching. I was working at the university at Coleraine with the PGCE students when I found out about a course being offered at the Magee campus in Derry the following September under the umbrella of extra -mural studies – a two year course on the History and Archaeology of Ulster. I signed up, not quite knowing what to expect. What did emerge was that the course involved six modules based on chosen aspects of Ulster history and archaeology, each lasting a term of the university year. The big shock was that you were expected to write an assignment on each topic which would be marked! I had a great two years, driving to Magee twice a week for lectures and going on field trips, in Derry, Donegal and Tyrone. Dr. Brian Lacy, who directed the archaeological survey of Donegal, was our lecturer for the archaeology module and he opened my eyes to a topic of which I had little knowledge – the pre- history and very early archaeology of Ulster.

Interest in the archaeology of Mountsandel at Coleraine area goes back a long time. In the 1880s flint axes were found ‘in a field behind Mountsandel Fort’ and in the 1920’s and 30’s a considerable number of flint axes from this area were presented to museum collections and recorded in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology. Of course none of these collectors recognised the particular importance of this site. It was not until the 1970s, when some of the fields behind the fort were scheduled to be developed for housing, that a team of archaeologists led by Professor Peter Woodman carried out a very significant dig over a period of 4 seasons – 1973, 1974, 1976 and 1977.

Google Earth View of Mount Sandel Woods, the Fort and the nearby River Bann and the Cutts

The excavations revealed a Mesolithic site that is now dated as going back 10,000 years (8000BC) and indicating the earliest settlers to Ireland. There had been a good deal of evidence of Mesolithic sites in Britain but no satisfactory evidence of their presence in Ireland until Peter Woodman made his important finds at what has become the most famous Mesolithic site in Ireland. The excavations produced a number of finds including evidence of settlement, tools the people used and what sort of economy they had. Post holes and stake holes situated in a small hollow behind the fort indicated where a number of huts had been placed, estimated at ten different huts. Woodman pointed out that several communities may have lived within fairly easy access of each other in the area south of the Bann estuary, Castleroe on the other side of the river being one. Woodman had also conducted a site investigation there at the same time as the Mountsandel dig and uncovered evidence of a similar kind.

A view of the top of the Fort at Mount Sandel

In the 1930s two small areas at the Cutts and at Loughan Island were dredged as part of a Bann drainage scheme undertaken by the Ministry of Finance and bone implements were recovered. It was assumed that these would probably have been from the Neolithic period. Also at Loughan Island during the same operation workman uncovered a tiny bronze disc made locally and now known as the Bann Disc. Two of my friends who live beside or near the east bank of the Bann above the Cutts have also found flint tools and stone axes in their gardens and one of their husbands found a bronze age sword when digging to construct a small pond. All these collections support other evidence that there was extensive settlement in the lower Bann valley over a long period.

This brings me to the object or objects which I have brought today. I live a short distance from the east bank of the River Bann and about a quarter of a mile from Mountsandel. During the time I was involved in the course at Magee, my husband and I were involved also in growing vegetables in our garden in Coleraine and lots of digging was done! One day I was out inspecting the potato crop and picked up what I now call a Bann flake. It has been officially described as a ‘butt trimmed flake’ with a sharp retouched blade on the right. The butt of this blade has been well trimmed indicating where it would have been hafted to a handle. In other words I had found a stone tool of the late Mesolithic period. Subsequently I found the other objects which I brought today – another Bann flake and a scraper – and many hundreds more pieces of flint in my back garden. Bearing in mind that the entire area close to the Bann would have been forest I like to think that the people who were living here would have been using this place in the woods as a mini factory, bringing the flint by boat from the coast at White Park Bay and fashioning their tools here. Most of the finds from my garden are debitage – the by-product of flint knapping – but I have several partially finished and completed stone tools.

Some fine flint tools from Kathleen’s vegetable garden

I have had great pleasure over the years in finding these flint tools, whether completed or discarded, in my garden. They have given me a bit more understanding of the fascinating archaeology of our North Coast and when it all began. This is in no small measure as a result of the work of Professor Peter Woodman who not only carried out the dig at Mountsandel but has been an outstanding archaeologist who has written extensively about his research and produced the seminal book on the Mesolithic period in Ireland very recently. At the launching of his book at the headquarters of the Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council Offices in 2016 he spoke passionately about the wonderful history we have around our north coast dating from Mesolithic, Bronze, Iron Age, Medieval and right through to the Plantation of Ulster, two world wars and through to modern times.

Sadly Professor Woodman died very suddenly a few weeks ago in Cork where he had been Professor of Archaeology at Cork University. He leaves a wonderful legacy of research and scholarship about his native land and particularly about Mountsandel and the River Bann.

14th February 2017