Presented by Dorothy Chandler

Robert Mackenzie, the grandfather of my late husband Douglas ,was born on the 28th August 1874 in Nairn in Scotland. He came from a long line of journeyman carpenters but when Robert grew up he was an apprentice grocer and eventually a Master grocer. After several moves and his marriage to Bertha, he worked in Belfast. He was introduced to the students in Belfast Technical Institute as an ‘Expert in the field of Window Dressing’ In 1912 he moved to Dublin and rented a ground floor shop in No.3 Cavendish Row, now Parnell Square, opposite the Gate Theatre. The publication ‘The Grocer’ described it as ‘The house for cooked meats, high-class provisions and Continental delicatessen’. By this time he and Bertha had a son and two daughters.

Modern view of Cavendish Row, opposite the Gate Theatre

The big adventure of Robert’s life was a trip to the United States in 1915 sailing out on the Lusitania. A relative had died there and he thought he might inherit a share of the estate. However when he got there closer relatives had beaten him to the claim. On 27th March he wrote to Bertha to expect him home by mid April but decided to extend his stay and do a bit of sightseeing and eventually sailed from New York on 1st May again on board the Lusitania. The liner was torpedoed ofF Kinsale on 7th May 1915 by a German submarine. He reckoned he was the last man into a lifeboat as he had been helping other people.

A contemporary drawing of the sinking of the Lusitania

There are several stories about the incident but he a was critical of how the ship was run. “It made only 20 mph having left Liverpool 86 firemen short and doubtless a great number deserted in New York as was nearly always the case”. Apparently the only boat drill the crew got was to sling the boats in the davits overboard ready for an emergency. This was where the boats were the morning of the disaster, there having been a boat drill the night before. Robert withdrew his criticism of the crew and their directions by the time he polished his account for the Grocer magazine. Perhaps he decided the Official Enquiry would deal with this and he might be called as a witness. This did not happen as the Official Enquiry was held ‘in camera’ to avoid the possibility of embarrassing information emerging about the presence of munitions on a civilian passenger ship, confirmation of which emerged when the wreck was inspected much later. Bertha only knew he had survived when he arrived at the front door.

World changing events again found Robert in their midst when the Rebellion in Ireland broke out in Dublin on Easter Monday 24th April 1916. Around noon the New Republic was proclaimed at the Post Office where the fighting became intense, extending to the north end of O’Connell Street. This was yards from Robert’s shop in Cavendish Row. Although Easter Monday was a public holiday it is likely the shop was open for business, unlike the bigger stores. Why else would Bertha and assistant Miss Moore have been sent home; they would hardly have come in to protect the shop against damage and looting as other city centre key holders did that Monday as news of the rising spread.

1916 photograph of the devastation in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street). Irish Times Archive

This and other information comes from two surviving undated notes from Robert to Bertha telling something of his last few days. On Tuesday 25th Robert sent a boy with a hand written note home to Bertha giving strict instructions not to leave the house. He wrote of three men being shot at the corner near the shop that afternoon (known that week as Deadman’s Comer) a detail which fixes Tuesday as the date of the first note, written on a blank invoice. His final sentence confirms the purpose of him and Mr. Carroll, his assistant, being in the shop “we must stay to keep looters away until Military is finished”. In his second note he writes “The window was broken but no attempt yet to take stuff. If they want it we won’t prevent them and you can rest assured we are safe and sound. We expect the military with us any minute”. As rebel rifle fire inflicted a heavy toll on the soldiers, much of their advance was halted, so they did not arrive.

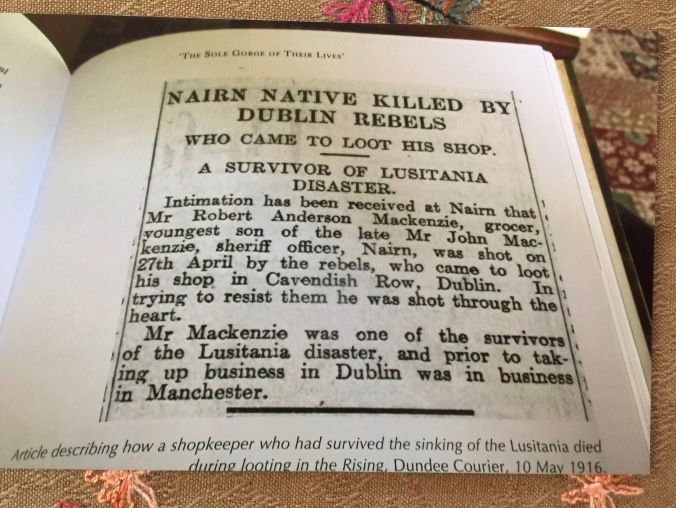

Robert was shot through the chest according to his death certificate dated Thursday 27th April 1916 having died on the way to the Mater Hospital. The Irish Times 2nd May confirmed his death at the hands of a sniper while sitting in his shop at midday but the family believe that he was shot by two looters when he would not let them into the shop. This seemed to be confirmed by his headstone in Nairn which says ‘shot by rebels in his premises’, The headstone in St. George’s cemetery in Dublin says ‘accidentally shot during the Rebellion in Dublin’

A newspaper report of Robert’s death.

When Robert died, Bertha was left to carry on a business in an Ireland in which English people and their families were very vulnerable. There was no option of returning to her family in Bury or Robert’s in Nairn. She had to keep the business open to provide for her family aged 15,12 and 10.. How could she retain customers if she advertised her husband had been shot dead resisting rebels. hence the local epitaph. She managed to keep the shop open successfully until 1930.

Robert’s descendants found closure on his life and marked the 100 years of his passing with an appropriate remembrance lunch at District One restaurant 3 Cavendish Row on 27th April 2016 followed by the placing of a wreath beneath Robert’s name on the 1916 Wall of Remembrance in Glasnevin Cemetery.

You can find information about Robert at the official Lusitania site http://www.rmslusitania.info/people/third-class/robert-mackenzie/

14th February 2017